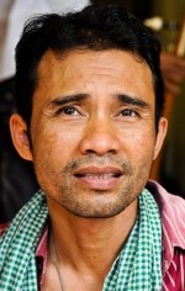

Hamilton alumnus and music major Jeff Dyer ’04 returned to Hamilton on April 3 for a discussion and performance with famed flute player, Arn Chorn Pond. Pond is a Cambodian-American who experienced the horrors of genocide when the Khmer Rouge took control of his native country and forced Pond into a child work camp.

As the subject of the documentary, The Flute Player, Pond has touched the hearts of many. He now travels around the globe, playing music and telling his story to provide inspiration and hope to war-torn countries.

Before Dyer introduced his friend, he began with a song, an offering to teachers and generations past. He played the kse diev, a wooden instrument known in Cambodia for more than a millennium. Unfortunately, the instrument was almost lost forever after the hostile take over of Cambodia by the Khmer Rouge. Luckily, one master escaped prosecution and the kse diev lives on today.

After the U.S. war with Vietnam, the Khmer Rouge invaded and took over Cambodia with the plan of turning it into an agrarian-based utopia. However, as Pond describes, utopia was the furthest thing from reality. Pushed out of the cities, Cambodians were placed in rural work camps, where they experienced starvation, systematic killing, and labor-intensive 18-hour days. It was in one such camp that Pond helplessly watched his younger brother and sister starve to death, before escaping into the jungle himself.

Pond eventually found a refugee camp, and it was here that he met his foster father, Peter Pond. Peter adopted Pond and two other boys, bringing them to Jefferson, N.H., for their new life (Peter and his wife, Shirley, would go on to adopt 16 more Cambodian orphans). Although Pond was grateful to his foster parents, the transition was difficult for him. He may have physically survived the Cambodian jungle, but emotionally, he was close to death.

Pond found minor relief by volunteering to join a music group, where he learned to play the dulcimer. In 1979, when the Vietnamese invaded Cambodia, the Khmer Rouge used Pond and the other children as decoys; replacing his dulcimer with a gun and putting him on the front lines. Pond couldn’t stand seeing innocent children turned into killers, and so he took his chances in the jungle, eventually finding refuge near the border. By the time he was rescued, he was severely malnourished, barely alive and weighing under 40 pounds.

Three months later Pond was living in New Hampshire and attending an American High School. Knowing two English words, rice and bathroom, Pond had a hard time acclimating. He soon learned a new word, monkey, the slur used by his classmates to describe him and his Cambodian foster brothers. Close to suicidal, he got in fights, pulled his teacher’s hair, broke a school window, and ran away.

Pond experienced a turning point when his father, who was notoriously tough, told him that, “you may have survived Cambodia, but if you don’t do what I say, you won’t survive the jungle of New Hampshire.” Peter promised Pond that he would not let him die alone, and encouraged Pond to share his story. Although Pond didn’t believe him, Peter was right when he said that if Pond opened up, the Americans would listen.

When he first shared his story, Pond never thought that his words would carry such power. He realized he had been wrong, and that, if the Americans knew about the horrors he experienced, they would care. It took him many years of telling his story to realize that “just talking is more powerful than the barrel of a gun.” Pond believes that it was opening his heart in this manner that saved his life. Continually struggling with the anger and fear within him, Pond never thought he would be as close to inner peace as he is today.

Dyer met Pond in 2004 when he traveled to Cambodia to study the music of the Khmer people thorough a Watson Fellowship.

Pond believes he would have died, emotionally if not physically, had he not shared his story. Pond continues to open his heart, sharing in the pain and suffering experienced by us all. During the Q&A, one community member implied that, despite her tragic past, she had not suffered as much as Pond. “Don’t compare it,” Pond softly replied, after hugging her, “pain is pain. You cry like I do. We laugh in the same way, we hurt in the same way.”

Founder of Children of War and the Khmer Magic Music Bus, Pond continues to spread hope and healing. He uses the unifying and restorative powers of music to remind the Cambodian people of their beautiful and rich history. To end the evening’s event, Pond played a song on his flute; filling the room with love, inclusion and of course, music.

Posted April 4, 2014