The untrod sands of the Egyptian Deserts hold a mystery much older than the construction of the pyramids: hundreds of naturally formed “desert eyes” unblinkingly turned toward the sky for tens of millions of years. Yet, despite their age, these structures have almost no topography, keeping them well hidden under the ever shifting landscape of aeolian sands. In fact, until the advent of Google Earth, these formations, which lie in the desert west of the Nile, were never studied.

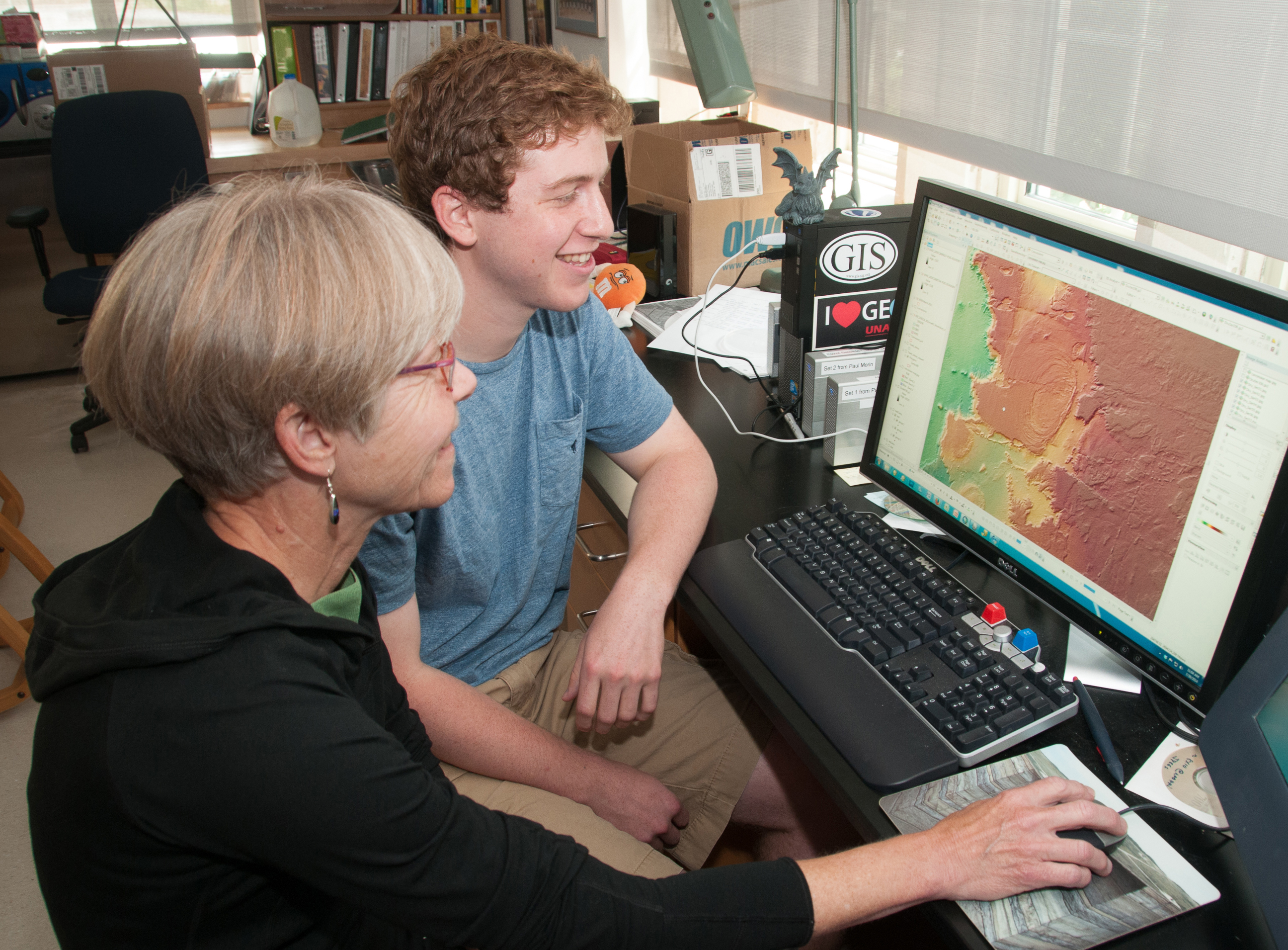

This summer, Josh Wolpert ’16, a geoscience major, is working with the Upson Chair for Public Discourse and Professor of Geosciences Barbara Tewksbury on the Desert Eyes Project, funded through the National Science Foundation (NSF). He expressed interest in pursuing geoscience research this summer to Tewksbury, who then offered him the opportunity to work as a student researcher on the project.

Tewksbury is a highly decorated instructor and geologist, recognized for her innovative teaching methods and emphasis on the intersection of the sciences and human issues. She has been part of the Hamilton community since 1978, during which time she has been honored with three named professor positions, held leadership roles in several professional geoscience organizations, and served as chair of the Geosciences Department.

Wolpert acknowledged that Tewksbury’s “Structural Geology” course gave him the fundamental tools for this summer’s research. However, he “knew very little about the geology of Egypt before this summer, so it took a little while to understand the rock formation names and general geology.” Nevertheless, although he had “limited knowledge about the type of methods [Tewksbury] uses and the types of conclusions she strives for,” he quickly became competent and engaged in the Desert Eyes Project.

Wolpert noted that “this summer, [they] have been particularly interested in a network of coalesced synclines near Assiut and Sohag in both the Eastern and Western Deserts.” Synclines are folded geological structures, typically caused by compressional stress, with younger layers closer to the center of the fold, forming the “pupil” of the eye.

Although the team is examining “enigmatic domes, basins, and polygonal structures in the young carbonate bedrock” in remote stretches of the desert, they are conducting their research from their lab in Upstate New York using high resolution satellite imagery. In the near future, the team will receive “geophysical data from an oil company in Egypt, adding valuable physical information to [their] research,” Wolpert noted.

Having received a 3-year grant from the National Science Foundation (NSF) in 2010, fieldwork began in 2011 and the project is currently in its third season. The Desert Eyes Project “is aimed at understanding the geometries, kinematics, and origin of these extraordinary structures,” as the Project’s site details.

Although Tewksbury and her team of Hamilton students have been the driving force behind the project, researchers and geologists around the globe are also involved. Our researchers are collaborating with Missouri University of Science and Technology, the University of Vermont, the University of Idaho, and the Egyptian universities of Damanhour, Alexandria, Assiut, Sohag, and Aswan.

The team has recently published a paper in Geology, which has been ranked for the past eight years by the Web of Science as the #1 geology journal. The paper, titled “Polygonal Faults in Chalk: Insights from Extensive Exposures of the Khoman Formation, Western Desert, Egypt,” appeared in the June issue and details the discovery of the world’s first on-land exposure of an unusual class of faults that have been previously studied only in undersea settings.

This year, Wolpert will present the results of the most recent work on the enigmatic synclines at the annual national meeting of the Geological Society of America in Vancouver, BC. Referring to the abstract of the poster they’re developing, Wolpert stated, “As it stands, we suggest a couple of potential models for the origins of the structures in this region.”

The team proposes either collapsed, coalesced paleokarst, the term for irregular erosion of limestone that produces fissures, sinkholes, underground streams, and caverns that were subsequently buried under sediment; or mobilization and flow of the underlying Esna Shale.

Wolpert compared their research to solving a crime; “We’re using hypotheses and evidence to examining a structurally complex area of Egypt, [in order] to discover how this area became deformed. The only difference,” he continued, “is that this crime occurred approximately 30-55 million years ago over the span of millions of years.”

“We have mapped the synclines and associated faults in Google Earth,” he explained, “to better understand the region, and have also examined scientific articles on the stratigraphy of Egypt [to determine] possible methods for the formation of the synclines.”

Wolpert will be continuing this research in Tewksbury’s Egypt seminar in the fall, and would like to pursue geoscience fieldwork and research at the graduate school level.

Josh Wolpert is a graduate of Chatham High School, NJ.

Posted August 19, 2014