Student Summer Research Goes International

Archaeological Digs in Belize

Margot Wilder ’27 returned to Belize for a second summer at the Mayan site of Xunantunich, conducting research with Northern Arizona University’s Belize Valley Archaeological Reconnaissance Project. She leveraged her past experience in a new role as a site supervisor, leading a team of students investigating a unique ball pit structure.

How has your experience influenced your academic/career aspirations?

I’ve always done some amateur archaeology as I’m from Arizona, one of the best places in the world for archaeology. But I never really saw a career path in it. When I came to Hamilton, I wanted to be a government major. But then I had this experience, and getting to work with professors, Ph.D. students, and master’s students, I was like, wait, there’s an actual future in this and I can really do it. I’m still doing government as a minor, and I’m starting to think a lot more about how those two connect. I’m considering going to law school and then working in antiquities law.

How did being in a different cultural environment shape your research?

One of the great things about working at Xunantunich is that it’s not just archaeologists at the site. It’s also one of the most visited archaeological sites in Belize. Many of the tour guides who work there are locals, and we have many local workers there as well who are doing all the conservation work. It’s amazing because you get talking to anyone there, and they’ll have a story of how they’re connected to the site. For many of them, it’s because they are the Mayan descendants of the people who lived there, and they can trace it back. We, as archaeologists, are trying to share what we know and have our work be a partnership, not something exploitative.

What’s something you learned during your fellowship that you didn’t expect to learn?

I went into this not fully expecting how much responsibility and agency I would have. Just being told, “You know what to do. Dig here and you make the decisions, and you interpret what we’re finding.” It was amazing to be thrown into that. Being a leader to these other students, it could be tough sometimes because I just finished my sophomore year. I felt really honored to be a supervisor, but it was also a real learning curve figuring out how to be a good leader and what that really means.

“Getting to work with professors, Ph.D. students, and master’s students, I was like, wait, there’s an actual future in this and I can really do it.”

Computer Science in Rome

With Professor Darren Strash of the Computer Science Department, Jack Kertscher ’26 embarked to Italy to conduct research alongside Professor Fabio Furini of Sapienza University in Rome. Over Italian coffees and pastries, the trio investigated what is known as the “temporal knapsack problem,” a scheduling task seeking to optimize spending certain resources during a certain amount of time. The project incorporated ideas from the disciplines of computer science and research operations.

How has this fellowship influenced your academic/career aspirations?

One of my biggest reasons for doing this over other opportunities was that I wanted to know whether or not a Ph.D. is something that would suit me. I’ve talked to Professor Strash about this extensively, and he encouraged me as I’d be working with Ph.D. students in a Ph.D. setting. I was able to see how well I could do and talk with Professor Strash, Professor Furinin, and the Ph.D. students about what it entailed and whether they saw that being a good avenue for me, knowing me as a researcher. I was proud of the work that I did, and I’m definitely strongly considering a Ph.D. in computer science pretty directly because of this program.

What is the value in researching computer science in a foreign setting?

Computer science is a field where research tends to be very segmented. You’ll have a researcher working one place and another researcher working in another. Part of our goal in going to Rome was to bridge these different areas of expertise and get a conversation happening, and that happens best in person. While it could be done over Zoom, we would not be able to sit down in a coffee shop and talk over coffee. We would not be working as well together in that situation.

How has this experience shaped how you think about being a global citizen?

Considering the political events that went on while I was there, there was a lot of talk about how they saw the United States and how we saw Italy. My biggest takeaway is that we often see each other more differently than we actually are, which was pretty cool to find out. Academically, socially, politically, there were many different times that even though I assumed that we would be coming from very different places, we ended up being very similar.

Lung Cancer Research in Italy

Bailey Leone-Levine ’27 spent her summer researching lung cancer and shadowing doctors at the University of Siena’s hospital in Italy. She has learned about how cancer affects different organs, laboratory techniques for genetic research, and the intersection between clinical practice and academic research.

What’s something you learned during your fellowship that you didn’t expect to learn?

One of my biggest takeaways is what it feels like to not speak the language, especially in a medical setting. I’ve observed surgeries and shadowed a bunch of doctors, and their first language isn’t English, so we’re both struggling to understand each other. This has really given me a deeper understanding of what it feels like to want to understand things in a medical context and not to be able to. It’s taught me how scary that can be. Going into medicine, understanding this is really important. A lot of people, especially in the U.S., get frustrated when people don’t know English, and they think that everyone should just know English automatically. I think having that deeper level of patience is really important.

What’s a moment that made you feel particularly excited?

One of my favorite moments was when I got to observe a double lung transplant operation, which is a really complicated surgery. I only got to see a little bit of it, but it was really interesting because it was the first surgery I’ve seen where they actually opened up the entire thoracic cavity, the part under your ribs where your lungs and heart are. It was the first time I’d ever seen a fully open chest surgery. I could see the patient’s heart beating. I could see his lungs going in and out. It was really, really incredible to see.

How did this experience challenge how you think about medicine?

In Italy, people really seem to love living and enjoying their lives. People sit on the street and talk and enjoy each other’s company. It’s not as go-go-go as in the U.S. Especially in the medical community in the U.S., it’s very much work all the time. Do what you need to do. Put your head down and do the work. In Italy, it’s more about doing the work so that you can enjoy it instead of doing it for the sake of doing it. Seeing that while being in this life-or-death side of medicine with cancer shows that appreciation for life. The work the doctors do at the hospital is not just fixing people for the sake of fixing people; it’s fixing people so that they can get back to this love of life that they all have here. That’s a perspective on medicine that I’ve never had before.

Climate Change in Iceland

For four weeks, James Maisano ’27 investigated the impacts of climate change on Iceland and how the island nation has been combatting these threats through a partnership with Reykjavik University. Maisano interviewed local Icelanders on their thoughts about climate change, learned about advanced carbon capture technology, and bore witness to the history behind the stunning landscapes of Iceland.

What’s a moment that made you feel particularly excited?

I actually got to visit Climeworks Mammoth plant! Climeworks and Carbfix are two of the companies I researched before coming to Iceland. Carbfix is a carbon storage technology. They take CO2 and combine it with water, then they inject it super deep underground and it forms into this salt rock. Climeworks is the company that captures the carbon. They have what looks like these giant fans that capture carbon on this substrate and then vacuum it into these giant tanks. Climeworks and Carbfix worked together on the Mammoth facility, which is the largest facility in Europe. It was super cool to see that in person. I got to see behind the scenes in one of the domes where they do the injection and see it happening. You don’t see that every day, and not many tours get to go in.

What’s something you learned during your fellowship that you didn’t expect to learn?

I learned how to get out there, reach out to people, take this leap, and face my fears. A lot of that was pretty intimidating to me, like when I asked the former president of Iceland a question. Just being able to do that is something that I would never imagine myself being able to do.

How did being in a different cultural environment shape your research?

Culturally, Iceland is a lot more accepting that climate change is happening, and they actually want to do something about it. Culturally in America, this is a pretty divided issue and a really sensitive topic. It was really great to see all these people agreeing and wanting to work together. That was something I kept in mind when I was talking to people and visiting sites.

“I learned how to get out there... take this leap, and face my fears. A lot of that was pretty intimidating to me, like when I asked the former president of Iceland a question.

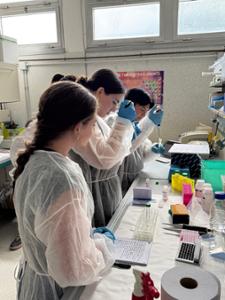

Gut Microbes in Pisa

Julia Afsar-Keshmiri ’26 ventured to Pisa, Italy, this summer to research the gut-brain access, the process by which bacteria and microbes in the intestine and gut influence the brain. She participated in two research projects, one studying how high-fat diets impact mice’s social skills and the other studying the circadian rhythms of mice with a neurodevelopmental disorder called CDKL5 deficiency disorder.

What’s something you learned during your fellowship that you didn’t expect to learn?

I learned a lot of new techniques both through observation and hands-on practice. My first couple of weeks were a lot of observation. Then as I started to get going, I said, “Hey, can I try this?” and that was a little bit scary at first to say. I’m learning that it pays to just ask for what you want. I sent cold emails and said, “Hey, I’m really interested in this topic. Here’s my CV. Do you have a spot in your lab?” and that worked out. And when I asked, “Hey, can I try this?”, the post-docs and Ph.D.s I’m working with were like “Of course!” and they’re excited that someone wants to try. So something I’ve learned throughout this experience is that I can ask for what I want and it’s fine either way.

What’s a moment that made you feel particularly excited?

It’s really cool to see how these techniques work, because you read papers and you say, “Oh, I’ve heard of this before,” and I can Google what it is, but you don’t realize until you watch someone do it. Like oh, they’re putting a live anesthetized mouse under the microscope and its brain is open and they’re literally taking pictures of a living brain. It’s very cool. There’s been a lot of a-ha moments from a technical perspective of “Oh, this is how this works!”

Why do you think this research is important?

I view this kind of research on the gut-brain access and the translation of it to medicine as a really cool way that we can manipulate our bodies in non-invasive ways to treat things. I’m just starting to learn about this, but I think it’s great that there’s a possibility to use things that are intrinsic factors in our lives — like what we’re eating, how we’re moving around, and how much we’re sleeping — in medicine.

“When I asked, ‘Hey, can I try this?’, the post-docs and Ph.D.s I’m working with were like ‘Of course!’ and they’re excited that someone wants to try.

Posted August 13, 2025